"It seemed to me that my mother held me in her womb, despite a profound rejection of motherhood, only to test her power over my father (who did not want to have children) and as an additional way to keep him bound to her."

With the rise of Nazism, Germany had become too dangerous for a Jewish revolutionary, and the couple moved to France, entrusting little Alexander to a Lutheran pastor and teacher. For five years little Alexander was sent only a few letters, of strictly essential content, from his mother. Not a single thought from his father. It was not until 1939 that the whole family could reunite in France, but unfortunately for a limited time. A few months later Sascha was interned at Le Vernet camp and later deported to Auschwitz, where he died in 1942. Alexander and his mother were instead interned in the camp for women and children in Rieucros where they escaped the massacre. The young Alexander managed, through the help of charitable organizations, to attend a high school in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, finding shelter in a home for refugee children. He found himself, more than once, having to spend nights in the woods to escape the Gestapo raids. He graduated in 1944.

After the end of the Second World War he began studying mathematics, initially at the University of Montpellier, and then arrived in Paris in the autumn of 1948 at the Ecole Normale Supérieure as a "free auditor". His first interest was in functional analysis (a branch that deals with the study of spaces of function) and he was then urged to move under the guidance of Jean Dieudonné and Laurent Schwartz, two of the leading French scholars of this branch of mathematics, He obtained his doctorate in 1953. In those years it seems that the two mathematicians entrusted Alexander with a list of fourteen problems, of prohibitive difficulty, asking him to solve one of his choice. After a few months of work, Grothendieck would present himself with the resolution of all fourteen problems.

He always had little satisfaction with institutional teaching methods. His enormous curiosity led him to develop, independently, a theory of measurement and integration; Only when he arrived in Paris did he learn that this theory had already been written and described by the mathematician Henri Lebesgue. Scrisse:

"Throughout my life as a mathematician, the ability to make explicit and elegant calculations has always come out on its own, as a by-product of a thorough conceptual understanding of what was happening. So I never worried whether what would come out would be suitable for this or that. I just tried to understand"

The consecration of his genius occurred in the period between the fifties and the seventies. In 1959 he was among the first hires in the newborn and Institut des Hautes Etudes Scientifiques (IHES) in Bures, near Paris where he began his studies in algebraic geometry, topology and number theory. His most important results were written in the treatise on algebraic geometry in the Eléments de géométrie algébrique (sometimes abbreviated EGA). His innovative ideas earned him the Fields Medal (the highest award in mathematics) in 1966.

Grothendieck, however, was not only an extraordinarily capable mathematician, he was also a fervent political activist: anti-militarist and pacifist, he strongly condemned the Vietnam War, while simultaneously repudiating communist ideas.

His political views led him not to travel to Moscow in 1966 in protest against Soviet totalitarianism, and he refused to withdraw Fields.

Almost twenty years later, in 1988, he was awarded the Crafoord Prize, run by the Swedish Academy of Sciences and awarded annually by the King of Sweden. Alexander flatly rejects the $250,000 prize with an open letter saying:

"The teacher’s salary and pension, which will begin next October, are more than adequate to my material needs; no money needed. As for the honours awarded to some of my works, I am convinced that only time will prove the fertility of new ideas or visions. Under these conditions, agreeing to participate in the game of awards and honours would mean giving my approval to a trend in the scientific world that I consider to be fundamentally unhealthy."

In 1970 Grothendieck, at the age of 42, left the official scene, resigning from the Institute where he worked. There are many reasons, one of them was the discovery that the Institute received funding from the French Ministry of Defence, an unforgivable fact for its anti-militaristic ideals.

Although he did not publish more research in a conventional way, in the 1980s Grothendieck continued to produce original works. Progressive social isolation led him to live the last thirteen years in total solitude. The material he wrote in his time as a hermit would amount to about 70,000 pages, many of which still to be deciphered, which added to the more than 20,000 preserved at the University of Montpellier form, perhaps, the most important mathematical treasure of the last centuries.

One of his colleagues recalled him as follows:

Grothendieck could be totally absorbed in mathematics. Sometimes, when he was thinking about a new theory, he had to remember to do even the most basic things, like eat and sleep. He had a strong interest in details and small things. He was opposed to snobbery, and so delighted with a comment by Henry Whitehead: «It is snobbery of young people to suppose that a theorem is trivial only because the proof is trivial.»

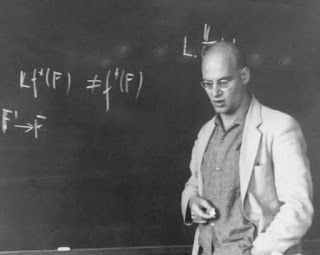

Credits photo American Mathematical Society

Post a Comment